Un commento dalla redazione di Episteme

Un commento dalla redazione di Episteme

L'acuta osservazione di Sabato Scala (che non è minimamente coinvolto nel presente commento alquanto "fantasioso"!) ci sembra confermare le ricorrenti ipotesi che in taluni gruppi "esoterici" romani e fiorentini circolassero, a proposito delle origini del cristianesimo, informazioni e interpretazioni assai poco ortodosse, aventi presumibilmente una radice "templare" (e il problema non è tanto se certe interpretazioni corrispondano nei fatti a una realtà che ormai ci sfugge, sepolta dalla polvere del tempo, ma se ad esse qualcuno abbia creduto - continui ancor oggi a credere! - in quale misura, e soprattutto con quali conseguenze nella storia).

Per quanto riguarda l'Ultima Cena in particolare [Che, come è noto, fu commissionata nel 1495, allo scopo di abbellire il Convento di Santa Maria delle Grazie a Milano, e portata a termine nel 1497. In pessime condizioni fino a poco tempo fa, è stata recentemente restaurata, vedi per esempio: http://www.cenacolovinciano.it/html/ita/restauro.htm, oppure:

http://www.italica.rai.it/principali/argomenti/arte/leonardo/segretoleo.htm], ricordiamo che nella quinta figura alla destra del Cristo qualcuno ha voluto intravedere un criptico riferimento al tema del "gemello", e nella quarta alla sinistra lo stesso pittore, che (unico tra i presenti) volgerebbe le spalle al Cristo non per caso, ma secondo un simbolismo che può facilmente ricollegarsi appunto ad altri atteggiamenti "anticristiani" contestati all'Ordine disciolto all'inizio del XIV secolo. Uno spunto analogo - ultima figura alla destra di chi guarda - sembrerebbe essere sviluppato anche nell'Adorazione dei Magi, composta tra il 1481 e il 1482, e attualmente conservata presso la Galleria degli Uffizi a Firenze. Manifestazioni di quel nicodemismo di cui parla Baldini in questa stessa sezione della rivista?

Il soggetto dei due Messia [Per il quale vedi anche gli scritti di David Donnini in Episteme N. 4, ma soprattutto Robert Ambelain (1907-1997): Jésus ou le mortel secret des Templiers, Ed. Robert Laffont, 1970, un libro di cui circola una versione italiana a cura di G. de Turris e S. Fusco. Notizie su questo interessante autore si possono trovare nel sito:

http://www.france-spiritualites.com/PARTRobertambelainexplorateurdessciencessecretes.html]

sembrerebbe ispirare pure altri dipinti di Leonardo (Vinci 1452 - Cloux

1519), quali la celebre Vergine delle Rocce [L'immagine

che precede è una delle tre versioni conosciute, la seconda in ordine

cronologico, che viene ricondotta proprio agli anni tra il 1494 e il 1497.

Si trova attualmente presso una collezione privata in Svizzera],

o il disegno che qui di seguito riproduciamo:

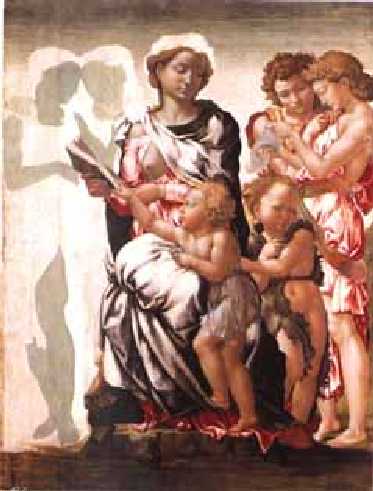

A questa storia [Che è lo spunto

di alcune opere di Tony Bushby, vedi http://www.thebiblefraud.com: opere

certo in qualche senso discutibili, ma non per questo del tutto prive di

fondamento! Riferiamo anche che esse sono state presentate dalla rivista

Nexus,

una lettura "inconfessabile" in ambito accademico, ma in verità

sempre stimolante, con le dovute cautele.] non sarebbe estraneo

l'altro grande artista cinquecentesco, Michelangelo (Caprese 1475 - Roma

1564). Viene presentata ai lettori in chiusura d'articolo la cosiddetta

Madonna

Pitti (il secondo bambino fa capolino dietro la figura della madre,

e non se ne comprendono né la necessità teologica, né

quella iconografica - più divertente, riteniamo, e non priva di

fondamento, l'ipotesi che si tratti di una specie di ammiccamento, un segno

d'intesa rivolto a coloro che fossero in grado di intenderlo), ma ovviamente

potrebbero portarsi ulteriori casi significativi concernenti tale autore.

Va da sé, il punto di vista "essoterico" scorgeva, può scorgere,

in siffatte raffigurazioni soltanto il Santo Bambino e ... San Giovannino,

vale a dire San Giovanni Battista piccolo. Ma, ad occhi non condizionati,

in esse apparirebbe rappresentata semplicemente una madre di due

bambini, un effetto rafforzato dall'assenza della pretesa seconda madre,

cioè di Santa Elisabetta. Si dovrebbe invero trovare strano che

essa sia generalmente assente anche in numerose composizioni del genere

di differenti autori, in una sorta di tradizione chissà come e da

dove originata (forse l'influenza dei due artisti qui citati?!). Per contro,

compare talvolta Sant'Anna, ossia ... la nonna di Gesù! Che la presenza

di questo San Giovannino fosse a qualcuno sgradita, in quanto avvertita

come impropria, è testimoniato per esempio dalla curiosa vicenda

che accompagnò la commissione della Vergine delle Rocce,

e che rammentiamo sinteticamente. Nel 1483 Leonardo accetta di dipingere

un quadro - destinato a un altare della confraternita dell'Immacolata Concezione

- che avrebbe dovuto rappresentare Dio in alto e la Vergine con il Bambin

Gesù al centro. Leonardo non rispettò le consegne ricevute

per il soggetto, e i committenti rifiutarono di corrispondere il compenso

pattuito con l'artista. Perplessità furono suscitate anche dalla

centralità di San Giovanni (che, ricordiamolo, è "patrono"

di Firenze, e ... della Massoneria), che diminuisce inevitabilmente quella

del Santo Bambino - anomala centralità viepiù sottolineata

dalla circostanza che il dito dell'angelo indica il primo bambino e non

il secondo - ma de hoc satis, c'è quanto basta per cominciare

a riflettere sulla validità di talune congetture storiografiche...

(La cosiddetta Madonna di Manchester, che viene fatta risalire

al 1510 circa, ad opera di qualche pittore strettamente collegato

a Michelangelo.)

* * * * *

Dal lettore Marco Zagari (marcozag@hotmail.com) riceviamo

il seguente interessante contributo.

> A proposito di eventuali credenze eretiche di Leonardo e di altri artisti del Rinascimento ipotizzate nel commento che Episteme ha dedicato alla nota di Sabato Scala, mi sembrerebbe importante accennare anche alla possibilità che si trattasse di eresie di tendenza cosiddetta Giovannita. Segnalo quindi ai lettori della rivista alcuni link in cui vengono illustrate simili ipotesi:

- http://www.stoke5399.freeserve.co.uk/leo/speculation-heresy.htm

(in questa pagina web si parla dei Mandei, e segnalo allora che http://www.mandaeans.org/frameset.htm è il sito ufficiale dei moderni Mandei dell'Iran e dell'Iraq; vi si illustra, fra l'altro, la dottrina Giovannita - mi è parso che diplomaticamente sorvolino sul fatto che secondo i Giovanniti il Battista fu ucciso proprio dai seguaci di Gesù)

- http://www.antiqillum.com/texts/bg/Qadosh/qadosh007.htm

(in quest'altra pagina, il secondo breve passaggio, che comincia con "The johannites ascribed...", è tratto dalla allocuzione di Pio IX che credo si intitoli "Multiplices inter machinationes")

- http://www.crystalinks.com/templars4.html

(vi si trova un altro passo, sempre molto breve, della stessa allocuzione, che spiega la confusione che a volte sembra sorgere fra il Battista e l'Evangelista).

Aggiungo che mi pare di ricordare così a orecchio, che un grado

dei Rosacroce si chiami "Intimo di S. Giovanni", e che i loro Sovrani si

chiamino Giovanni I, Giovanni II etc.

* * * * *

Per una buffa coincidenza, proprio poco dopo aver redatto il precedente commento, ci è pervenuta la seguente notizia (da CRISIS Magazine - e-Letter, 25 luglio 2003, tramite la "Lista di informazione su cattolici e politica sotto la protezione di Giuseppe Tovini. Per contattare l'amministratore scrivere a botti.d@tiscali.it"):

> Molte persone mi hanno chiesto di The Da Vinci Code - il romanzo best-seller in voga che afferma che la Chiesa Cattolica ha nascosto la "verità" su Gesù. Tra le altre cose, il libro sostiene che Gesù sposò Maria Maddalena ed ebbe figli da lei. Questo libro è un attacco violento su tutta la scala al Cristianesimo e condurrà molte persone fuori strada. Nel prossimo numero di settembre di CRISIS smonteremo il Da Vinci Code, dimostrando il pregiudizio anticristiano del romanziere e la ricerca scandalosamente povera.

Non abbiamo letto il romanzo in questione, e non sappiano quindi quanto

meriti per esempio le ulteriori critiche che riportiamo qui di seguito

in modo esplicito (per comodità dei nostri lettori e ... a "futura

memoria", vista l'estrema precarietà delle informazioni circolanti

in rete), assieme a una presentazione invece positiva, ma siamo del parere

che, seppure talvolta mal utilizzati, certi "ingredienti" possano sostanzialmente

corrispondere alla realtà di fatti che hanno uno spessore nascosto

che la ricerca storica ufficiale non riesce quasi mai a scalfire, spesso

per

principio...

- - - - -

http://books.guardian.co.uk/reviews/crime/0,6121,1005850,00.html

Crime - Signs for the times - Saturday July 26, 2003 - The Guardian

Mark Lawson finds that nothing is left to chance in Dan Brown's ludicrous but gripping bestseller, The Da Vinci Code (by Dan Brown 454pp, Bantam, £10.99)

The conspiracy thriller, it can be argued, is the purest kind of bestseller. The premise of such books is that there's no such thing as a random happening; meanwhile, though bestsellers aren't exactly conspiracies, most huge publishing successes can be traced back to a web of connected events, so that form and content collide to an unusual degree.

For example, Peter Benchley's Jaws was probably a good enough story to find readers at any time, but became a mid-70s sensation because the implications of the plot - horrible, sudden death in a holiday resort - reflected the neuroses of an affluent American generation enduring both a cold war and an oil war. Helen Fielding spotted that young unmarrieds were a social grouping without a literature; Allison Pearson noticed the same gap for working mums.

And coming up to two years after September 11, 2001 - roughly the time it takes conventional fiction publishing to respond to cultural shifts - what did we find unstoppably atop the American fiction charts? Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code, 450 pages of irritatingly gripping tosh, offers terrified and vengeful Americans a hidden pattern in the world's confusions.

When bad things happen, Brown reassures us, it is probably because of the machinations of a 1,000-year-old secret society which is quietly running the world, though often in conflict with another hidden organisation. There are probably a couple of verses in Nostradamus predicting the triumph of The Da Vinci Code: "As the painted French woman smiles/The Brown man will top the heap", or something similar. Certainly, the novel's success can be attributed to those who read Nostradamus and believe that the smoke from the blazing twin towers formed the face of the devil or Osama bin Laden.

What happens in The Da Vinci Code is ... alert readers will have noticed a delay in getting round to plot summary, but it takes time to force the face straight. Anyway, my lips are now level, so let's go. Art expert Jacques Sauniere is discovered murdered in the Louvre, having somehow found the strength in his last haemorrhaging moments to arrange his body in the shape of a famous artwork and leave a series of codes around the building.

These altruistic clues are interpreted by Robert Langdon, an American "professor of religious symbology" who, by chance, is visiting Paris, and Sophie Neveu, a French "cryptologist" who is the granddaughter of the artistic cadaver in the Louvre.

As they joust with authorial research - about the divine proportion in nature and the possibility that the Mona Lisa is a painting of Leonardo himself in drag - a thug from the secretive Catholic organisation Opus Dei, under orders from a sinister bishop, is also trying to understand the meaning of the imaginative corpse in the museum.

It all seems to be connected with the Priory of Sion, a secret society. Reading a book of this kind is rather like going to the doctor for the results of tests. You desperately want to know the outcome but have a sickening feeling about what it might prove to be. In this case, the answer was as bad as I'd feared.

Recently, crime and thriller fiction has been increasingly easy to defend against literary snobs at the level of the sentence. Not here. Brown keeps lugging in nuggets from his library: "Nowadays, few people realised that the four-year schedule of modern Olympic Games still followed the cycles of Venus." Otherwise, he favours clunking, one-line plot-quickeners: "Andorra, he thought, feeling his muscles tighten." French characters speak in American, while occasionally throwing in a "précisement" to flap their passport at us.

Criticism won't hurt Brown, who can probably now buy an island with his royalties and a second one with the film rights. The author has, though, recently found himself on the end of an unwanted conspiracy theory: another writer has accused him of plagiarism. In strongly denying this, Brown employed a striking defence: that the points of overlap were clichés which were part of the genre of the thriller and therefore belonged to no one writer.

This admission of unoriginality may further anger readers and writers annoyed by seeing something as preposterous and sloppy (one terrible howler involves the European passport system) as The Da Vinci Code on its way to selling millions. But the success of this book is due not to the writing but to post-9/11 therapy. It tells so many Americans what they want to hear: that everything is meant. In doing so, Brown has cracked the bestseller code.

Mark Lawson's novel Going Out Live is published by Picador.

- - - - -

http://www.wired.com/news/culture/0,1284,58378,00.html

Ever looked at the Mona Lisa and wondered why he's got such a goofy

grin?

Yes, we do mean he.

Evidently, Mona isn't quite the woman art historians thought she was.

But only those who know the secret code can look at Leonardo da Vinci's

famous portrait and see the happy hermaphrodite that lurks within.

Dan Brown's latest novel, The Da Vinci Code, published by Doubleday Books, is about the famous Renaissance artist and the oblique references to the occult contained in his equally famous paintings. It's also about ancient secret societies, modern forensics, science and engineering, and the history of religion.

Most of all The Da Vinci Code is about the history of encryption -- the many methods developed over time to keep private information from prying eyes.

The novel begins with Harvard symbologist Robert Langdon receiving an urgent late-night phone call: The elderly curator of the Louvre has been murdered inside the museum.

Near the body, police have found a secret message. With the help of a gifted cryptologist, Langdon solves the enigmatic riddle. But it's only the first signpost along a tangled trail of clues hidden in the works of Leonardo da Vinci. If Langdon doesn't crack the code, an ancient secret will be lost forever.

Brown's characters are fictional, but he swears that "all descriptions of artwork, architecture, documents and secret rituals in this novel are accurate."

The author provides detailed background on the novel's historic basis on his website, but he suggests readers finish the book before reviewing the site, which gives away some of the plot's twists.

The book's publicity hints darkly that the story lays bare "the greatest conspiracy of the past 2,000 years." Perhaps, but anyone who is interested in conspiracy theories won't find anything new here. The basic thesis is that da Vinci was a member of a secret society charged with protecting the true history of Christianity until the world is ready to hear it. This theme has been explored in depth in other books such as Holy Blood, Holy Grail and The Messianic Legacy, both written by Michael Baigent, Henry Lincoln and Richard Leigh.

Where The Da Vinci Code does shine -- brilliantly -- is in its exploration of cryptology, particularly the encoding methods developed by Leonardo da Vinci, whose art and manuscripts are packed with mystifying symbolism and quirky codes.

Brown, who specializes in writing readable books on privacy and technology, cites da Vinci as an unheralded privacy advocate and encryption pioneer. His descriptions of da Vinci's cryptology devices are fascinating.

Throughout history, entrusting a messenger with a private communication has been rife with problems. In da Vinci's time, a major concern was that the messenger might be paid more to sell the information to adversaries than to deliver it as promised.

To address that problem, Brown writes that da Vinci invented one of the first rudimentary forms of public-key encryption centuries ago: a portable container to safeguard documents.

Da Vinci's cryptography invention is a tube with lettered dials. The dials have to be rotated to a proper sequence, spelling out the password, for the cylinder to slide apart. Once a message was "encrypted" inside the container only an individual with the correct password could open it. This encryption method was physically unhackable: If anyone tried to force the container open, the information inside would self-destruct.

Da Vinci rigged this by writing his message on a papyrus scroll, and rolling it around a delicate glass vial filled with vinegar. If someone attempted to force the container open, the vial would break, and the vinegar would dissolve the papyrus almost instantly.

Brown also brings readers deep into the Cathedral of Codes, a chapel in Great Britain with a ceiling from which hundreds of stone blocks protrude. Each block is carved with a symbol that, when combined, is thought to create the world's largest cipher.

"Modern cryptographers have never been able to break this code, and a generous reward is offered to anyone who can decipher the baffling message," Brown writes on his site.

"In recent years, geological ultrasounds have revealed the startling presence of an enormous subterranean vault hidden beneath the chapel. This vault appears to have no entrance and no exit. To this day, the curators of the chapel have permitted no excavation."

Brown specializes in literary excavation. His previous books have all involved secrets -- keeping them and breaking them -- and how personal privacy slams up against national security or institutional interests.

He's written about the National Reconnaissance Office, the agency that designs, builds and operates the nation's reconnaissance satellites. He's also written about the Vatican and the National Security Agency. Brown's first novel, Digital Fortress, published in 1998, details a hack attack on the NSA's top-secret super computer, Transltr, which monitors and decodes e-mail between terrorists. But the computer can also covertly intercept e-mail between private citizens. A hacker discovers the computer and takes it down, and demands that the NSA publicly admit Transltr's existence or he'll auction off access to the computer to the highest bidder.

"My interest in secret societies sparks from growing up in New England, surrounded by the clandestine clubs of Ivy League universities, the Masonic lodges of our Founding Fathers and the hidden hallways of early government power," Brown said. "New England has a long tradition of elite private clubs, fraternities and secrecy."

To encourage his readers to discover the joys of cracking code, Brown has created an Internet-based treasure hunt based on The Da Vinci Code that involves Google searches, code cracking, e-mail missives and low-level password hacking (http://www.danbrown.com/).

Winners will receive a prize that, Brown said, involves "something money

can't buy." He declined to provide details, saying that he wants winners

to be surprised.

(L'Adorazione dei Magi)